-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage

La lecture à portée de main

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisRecovering Lost Footprints, Volume 2 , livre ebook

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisEn savoir plus

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

En savoir plus

Description

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part I. Peninsular Mayas

1. How Peninsular Narrative Happened

2. Jorge Cocom Pech, Javier Gómez Navarrete, and Isaac Carrillo Can: Three Generations of Writers Reconfiguring Peninsular Maya Cosmovision

3. A Prolific Woman Novelist Takes Center Stage: Marisol Ceh Moo

Part II. Emerging Narratives in Chiapas

4. Chiapanecan Indigenous Writers Begin to Tell Stories

5. How It All Began in Chiapanecan Narrativities

6. Josías López Gómez: A Prolific Narrator

Conclusion

Notes

Works Cited

Index

Sujets

Informations

| Publié par | State University of New York Press |

| Date de parution | 30 novembre 2018 |

| Nombre de lectures | 0 |

| EAN13 | 9781438472607 |

| Langue | English |

Informations légales : prix de location à la page 0,1698€. Cette information est donnée uniquement à titre indicatif conformément à la législation en vigueur.

Extrait

Recovering Lost Footprints

RECOVERING LOST FOOTPRINTS

VOLUME 2

CONTEMPORARY MAYA NARRATIVES

ARTURO ARIAS

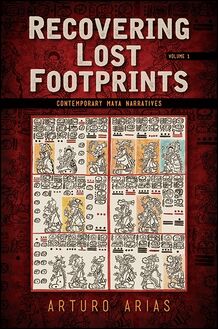

Cover image: Láminas 8 y 9 del Códice de Dresden, dibujado por Lacambalam (pages 8 and 9 of the Desden Codex, drawn by Lacambalam). © Lacambalam (Jens Rohark).

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

© 2018 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Arias, Arturo, 1950– author.

Title: Recovering lost footprints. Volume 2, contemporary Maya narratives / Arturo Arias.

Other titles: Contemporary Maya narratives

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016058082 (print) | LCCN 2017018899 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438472607 (e-book) | ISBN 9781438472591 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Maya literature—History and criticism. | Guatemalan literature—History and criticism.

Classification: LCC PM3968 (ebook) | LCC PM3968 .A75 2017 (print) | DDC 897/.42709—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016058082

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction

PART I Peninsular Mayas

1. How Peninsular Narrative Happened

2. Jorge Cocom Pech, Javier Gómez Navarrete, and Isaac Carrillo Can: Three Generations of Writers Reconfiguring Peninsular Maya Cosmovision

3. A Prolific Woman Novelist Takes Center Stage: Marisol Ceh Moo

PART II Emerging Narratives in Chiapas

4. Chiapanecan Indigenous Writers Begin to Tell Stories

5. How It All Began in Chiapanecan Narrativities

6. Josías López Gómez: A Prolific Narrator

Conclusion

Notes

Works Cited

Index

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I stated in the acknowledgments to the first volume that this book had been a long time in the making. This has held true for the second volume as well. In their conception, there was no separation between the two volumes. They were both researched, and written, as if they were only one. Only time and girth divided them, unlike volume 3—still being written—in which I move away from Maya territory to critique non-Maya Mexican Indigenous narratives. As I wrote without barriers of any kind, it became all too evident that the manuscript had grown to a length that would be inadmissible for most presses. Just in case, I tested the waters, and my suspicion was confirmed. That led to an operation such as the one that separates Siamese twins. In dividing the work on Yucatecan and Chiapanecan Maya literature from that of Iximuleu, I realized I would need a new introduction as well as new conclusions for what became volume 2. This discovery was a blessing. It enabled me to plunge deeper into my apprenticeship of Indigenous knowledges, and theories written about them. Newer readings also led to establishing a comparison between the critical production of Native Americans and that of Indigenous peoples in Latin America. These have strengthened volume 2 significantly. The revisions needed in the analyses transformed this volume into one that could easily stand on its own, without readers having seen the first one.

In this logic, when it comes to thanking people, those already named in the acknowledgments to the first volume certainly carry over to this one as well, given that the two were written as one. Since the completion of the first volume, the novelties would include the cordial welcome I have received at SUNY Press. Beth Bouloukos, first, and then Amanda Lanne-Camilli, believed in my project from the start. Beth encouraged me to divide the original manuscript encompassing volumes 1 and 2 into two volumes. She was also proactive in production details, to guarantee that the end-product would be the best volume possible. As of spring 2017, Amanda became directly involved. Since then we have developed an unusually close collaboration that may yield still more fruits. I consider my relationship with SUNY Press especially privileged.

Between volumes I also switched institutions, from the University of Texas at Austin, to the University of California, Merced. My new institution graciously offered me the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Professorship. It goes without saying that this support has been critical in providing the time and opportunities to consolidate all aspects of volume 2, as well as the upcoming volume 3. The fast completion of volume 2 as a book that can stand on its own would not have been possible without this support.

I would also like to briefly mention Yukateko Maya writer Isaac Carrillo Can here. He tragically passed away in November 2017 as this manuscript was being completed. He represented some of the best qualities of young, determined, creators. His energetic presence, enthusiasm, passion, and promise of splendid work to come left not only his family shrouded in pain and grief, but also the broader Maya family of sympathizers, readers, critics, publishers, and fellow writers. He is greatly missed. The analysis of his novel in chapter 2 is an homage to a young talent lost way too early, and a reflection of the life he may have lived.

Finally, I want to thank once more my wife, Jill Robbins. Each time we converse on any topic, I witness anew how delightfully original her mind is. Jill’s habit of looking at everything from a uniquely singular perspective, and automatically analyzing it out loud, not without healthy doses of irony, always enriches my approach to my work. She is the perfect companion: affectionate, nurturing of everything that lives, from children to dogs to tarantulas, funny, laughing, full of humor at the chaos of living on this planet—and surviving our present-day rulers. Her mind, always working at full speed, day in and day out, enriches my own, teaching me uniquely innovative ways to approach my work.

Introduction

In the introduction to the first volume of this same topic, I claimed that academic debates on decolonization in the Global North had failed for the most part to engage Native American and Indigenous theories and knowledges. In subsequent articles and conference presentations I dwelled further on the critical importance of Indigenous knowledges to analyze their literary production. Peruvian Quechua or Qhiswa scholar Pablo Landeo Muñoz had already stated “al aproximarnos al mundo andino nos encontramos con una realidad donde el concepto pacha (mundo, cosmos, tiempo, acontecimientos y seres) responde a epistemes divergentes del concepto occidental de ‘mundo’” ( Categorías andinas 18; when we approach the Andean world we find ourselves with a reality where the concept pacha [world, cosmos, time, events and beings] responds to divergent epistemes from the Western concept “world”). This issue became all too clear for me after participating in the Abriendo Caminos Conference on History, Society, and Literature in Chiapas that took place at the Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas in Jobel (San Cristóbal de las Casas) the first weekend of April 2017. Abriendo Caminos José Antonio Reyes Matamoros is a civil society of Chiapanecan Maya writers and academics. A significant recognition of their open-mindedness is their honoring a non-Maya personality, José Antonio Reyes Matamoros, who directed the first creative writing workshop for Mayas in 1997, as explained in chapter 4 of this volume. Reyes Matamoros’s widow, Maura Fazi Pastorino was honored at the end by a poetry reading where Maya and Mestizo poets read their work in intermixed fashion. Later that same night, informal conversations washed down with boj or mescal with some of the key conference participants, such as Antonio Guzmán Gómez, Mikel Ruiz, Ruperta Bautista, Canario de la Cruz, Ary Uriel López, Ulises Gómez Vásquez, Ligia Peláez, and Fabiola Carrillo, comprehensively embraced the critical importance of better understanding Indigenous knowledges to fully analyze their present-day cultural production.

It has been self-evident for at least a good century that we cannot truly separate literary and cultural production as such from the knowledges that inform creative efforts, as these record personal and community experience. The distinctive social imaginaries informing authors are either interpellated by those very narratives or else reconfigured by the fictional or symbolic acts themselves. After all, social imaginaries are “first-person subjectivities that build upon implicit understandings that underlie and make possible common practices” (4), as Dilip Parameshwar Gaonkar argued, if in a different sense than my own understanding. When restricting ourselves to literary production we know that, as systems of representation, all forms of writing, regardless of their origin, are always written within a sociopolitical, cultural, historical, and ecological context, informed as well by issues of gender, race, sexualities, and other variants. It is also a given that texts (or any kind of cultural object, for that matter) go through processes of production, circulation, and consumption, procedures that are inf

-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Actualités

-

Lifestyle

-

Presse jeunesse

-

Presse professionnelle

-

Pratique

-

Presse sportive

-

Presse internationale

-

Culture & Médias

-

Action et Aventures

-

Science-fiction et Fantasy

-

Société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage